"What realy knocks me out is a book that, when you're all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it. That doesn't happen much, though."

The words of Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye.

The words of Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye.

Well, Holden didn’t live in the age of twitter.

After reading Jon Bassoff’s first two novels, I was salivating over his latest release, The Disassembled Man. It is the story of Frankie Avicious, a sadly tragic, sociopathic character desperate to get what he feels he's deserved. Bassoff took this character, cut off his skin, sewed me up inside, transplanted half a lobe of his brain into me skull, and sent me on my way for 300 pages or so.

I reached out to Bassoff after finishing the book, and he graciously agreed to be interrogated. Thanks to Jon for his answers which definitely enrich the experience of reading his books.

Your style has been described as Mountain Goth, and your bio reports you live in a Colorado Ghost Town. How does the mountain setting you live within guide your stories?

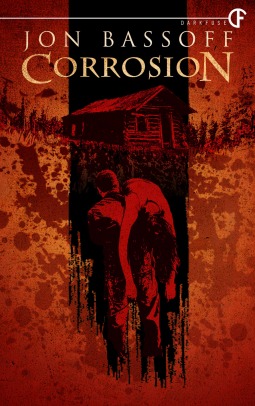

Yeah, I spend a lot of time thinking about that sense of place. Most of the towns I’ve created have been composites of lonely, derelict places I’ve spent time in. In Corrosion, for example, the creepy mountain town was a composite of places like Ward, Gold Hill, and Leadville, all very different mountain towns, but each with a literary element I was looking for. But more so than physical terrain, the setting usually represents some void in my characters’ psyche. There is always a menacing emptiness which, eventually, is acted out by my characters.

All three of your books are different, yet they all seem to occur in the same world, within the same universe. (For example, Frankie Avicious could easily find a home in Factory Town.) How much, if any, did you mean to have your three novels connect?

I’ve never had any interest in writing a series, mainly because I get bored very quickly. Also, it would be hard to spend more than a year with my characters, as you might imagine. But I do think there are common themes that run through all my novels—repressed memories, generational abuse, repetition of sins to name a few. Most of my characters have nothing to lose, and they have no meaningful sense of connection. And without that connection—anything can happen.

Your characters. Holy shit. They are so tragically humane, at times monstrous and often sadly evil. You suck readers into their brains, never step out of character, and trust the reader will realize they are dealing with an untrustworthy and deranged narrator.

The author that made me want to become a novelist was Jim Thompson. When I read The Killer Inside Me, I was stunned. I’d never read anything like it before. All of those things you said—monstrous, untrustworthy, deranged—could describe Thompson’s narrators. I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to explore the unrestrained Id. While my books aren’t traditional mysteries, I’ve always tried to challenge the reader to figure out who the hell the narrator really is. In the real world, every person is unreliable and untrustworthy. We’ve all got demons, sins, and insecurities we try to hide and repress. My narrators are no different, except that their demons and sins tend to be monumental.

The author that made me want to become a novelist was Jim Thompson. When I read The Killer Inside Me, I was stunned. I’d never read anything like it before. All of those things you said—monstrous, untrustworthy, deranged—could describe Thompson’s narrators. I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to explore the unrestrained Id. While my books aren’t traditional mysteries, I’ve always tried to challenge the reader to figure out who the hell the narrator really is. In the real world, every person is unreliable and untrustworthy. We’ve all got demons, sins, and insecurities we try to hide and repress. My narrators are no different, except that their demons and sins tend to be monumental.

Your metaphors are long, detailed, full of wit, but they also create tone, develop characters, and add to a setting that seems larger than life. How much work does this take? Do they just slip right from your mind to your fingers, or do they require lots of resizing and editing.

Well, growing up I read my share of Raymond Chandler and other crime fiction writers and enjoyed those metaphors and similes—no matter how heavy handed they were. For The Disassembled Man, I wanted to play off that tradition. I wanted to make them as goofy and ridiculous as possible because our protagonist, Frankie, sees the world as nothing more than a joke. In some ways, that’s what’s so terrifying about him. So he says things like: “As tired as an anemic anaconda after eating an oversized antelope.” In my other novels, I’ve tried to be a bit more subtle. Sometimes, I think, using too many metaphors and similes makes the reader hyper aware of the author and how hard he’s trying.

What music do you listen to as you write, if any? Or, what music do you feel captures the tone of your books? Who do you want to do the movie soundtracks?

I have a tough time focusing if I’m listening to music with words. So mainly, I listen to classical music. Brahms, Sibelius, Vaughn Williams, Rachmaninoff. Guys like that. When I wrote Corrosion, however, I wore out the soundtrack of Paris, Texas. Ry Cooder is just brilliant. If Corrosion indeed becomes a film, I would love to have him do the music.

Your first two novels have the characters’ dialogue inside the chapters not as quotes, but as part of the passage. It is done so well that it felt natural by page two, and sucked me deeper into the character. What was the inspiration for this? Did any editors or beta-readers try to talk you out of it?

My narrators tend to be unreliable, so I decided that eliminating the quotation marks added to this sense of unreliability. Sometimes it becomes difficult to determine if the character is actually speaking or just fantasizing. Having quotes gives off a sense of reliability. This is exactly what he said. I wanted to eliminate that. Also, I thought it added a certain starkness to the page, which I was going for. But it was distracting enough for enough readers that I’ve gone away from that and I don’t know if I’ll return.

As I read about the meat factory in The Disassembled Man, I couldn’t help but think of Sinclair  Lewis’s comment about his novel The Jungle; “I aimed for their hearts, and hit their stomachs.” Your book featured some of the same type of slaughter-house scenes, only you have portrayed humans seemingly as doomed as cattle at the end. Are you vegetarian? Ever been in such a slaughter-house?

Lewis’s comment about his novel The Jungle; “I aimed for their hearts, and hit their stomachs.” Your book featured some of the same type of slaughter-house scenes, only you have portrayed humans seemingly as doomed as cattle at the end. Are you vegetarian? Ever been in such a slaughter-house?

Lewis’s comment about his novel The Jungle; “I aimed for their hearts, and hit their stomachs.” Your book featured some of the same type of slaughter-house scenes, only you have portrayed humans seemingly as doomed as cattle at the end. Are you vegetarian? Ever been in such a slaughter-house?

Lewis’s comment about his novel The Jungle; “I aimed for their hearts, and hit their stomachs.” Your book featured some of the same type of slaughter-house scenes, only you have portrayed humans seemingly as doomed as cattle at the end. Are you vegetarian? Ever been in such a slaughter-house?

I live near a lot of slaughterhouses, but I have never been inside. They make it almost impossible to see what’s actually happening, for reasons you can imagine. So I relied on plenty of research. They are obviously pretty gruesome places. Better not to think about where our food is coming from. And, yeah, the slaughterhouse was an ongoing metaphor for the tragic destiny that awaits some of the characters. And of course, there is the reality that working in a place like that must take an incredible spiritual and emotional toll. But no, I am not a vegetarian. My sensory impulses, I guess, outweigh my morality and logic.

I do feel there is a deep empathy for the human condition in your novels, and a love for humanity in their tragically damaged stated, but imagine this: One hundred years from now and your work is being studied at University of Colorado. You walk into a lecture entitled: "Is God Dead in a Bassoff novel, or Just Insane?” What kinds of things do you hear in the discussion? (things to consider, your fabulous passage: “And then silence, God hanging from a noose.”)

I do feel there is a deep empathy for the human condition in your novels, and a love for humanity in their tragically damaged stated, but imagine this: One hundred years from now and your work is being studied at University of Colorado. You walk into a lecture entitled: "Is God Dead in a Bassoff novel, or Just Insane?” What kinds of things do you hear in the discussion? (things to consider, your fabulous passage: “And then silence, God hanging from a noose.”)

Oh, man! That’s got to be the best question I’ve ever been asked in an interview. Please, University of Colorado, create this course! I don’t know what I’d hear in the discussion, but I do know that my characters have a very complex relationship with God. I think they badly want to believe in a power greater than them, but the landscape they inhabit seems bereft of any biblical blessings. One of my favorite quotes is from a Tom Waits song: “Don’t you know there ain’t no devil, there’s just God when he’s drunk.” So I guess my characters would lean toward God being insane as opposed to dead. I mean, if God lives inside of each of us, that would certainly give credence to the insane God theory. In some ways, however, I think they are hoping that God is dead, or that God doesn’t exist, because they know any type of judgement wouldn’t be pretty.

My wife has tried, believe me she has. She doesn’t share my passion for depravity, though, so it’s been tough for her to wade through those pages. My parents and sister have read my stuff and they haven’t disowned me. As far as my students—that’s an interesting one. A lot of them have read the books and dug them, but it’s not so easy for them to separate the author from the narrator. After reading, I had one student tell me, “Mr. Bassoff, I will never look at you the same way.” Do they think I’m a sociopath or a murderer? It’s hard to tell. I’m just thankful that no parent has tried to get me fired.

All of your books seem to feature characters who can’t escape from something in their past. Any chance a character in your world can defy their past and become heroic in a traditional sense?

All of your books seem to feature characters who can’t escape from something in their past. Any chance a character in your world can defy their past and become heroic in a traditional sense?

I’ll answer this question as simply as I can. Redemption isn’t my thing.

Darkfuse is a tremendous publisher of dark fiction, and a culture onto its own with it subscription services, reader community, and what seems like a well-knit darkfuse author network . (y’all seem part of a secret society, in other words, with Gifune bringing the bagels each day and Meikle having to skype himself in from Scotland). What’s it like to work with Darkfuse?

It’s the best. Shane Staley is a tremendous publisher—he’s very receptive and innovative, and is always looking for ways to promote the authors and the “brand.” Greg Gifune is such a tremendous writer in his own right, and he’s been my personal psychologist when I’ve been insecure about the stories I’ve allowed into the world. Then you’ve got Dave Thomas, a fantastic editor, and Zach McCain who is one of the best designers out there. It’s just the perfect little press. I’m tremendously proud and humbled to join all the great writers at DarkFuse.

The Incurables comes out in the fall, and I’ll be reading it soon as possible. What can I expect?

Well, the main character is based on a historical person—Walter Freeman Jr. He was the guy who revolutionized the lobotomy in the United States. He was this tragic figure—a doctor who really thought he was doing good, really thought he was saving the world. He used to drive across the country in his Lobotomobile, giving lobotomies to anybody and everybody who was suffering from mental ailments. Of course, most of his patients ended up being more damaged after the surgery. Still, until the day he died, he was convinced he had done the right thing. He used to contact all of his former patients—and there were tens of thousands of them—trying to convince himself that he had saved them. In addition to Freeman, there is a man who is convinced that his son is the Messiah, a sociopathic prostitute, and a group of machete wielding brothers. Typical Hallmark Channel stuff, you know? Actually, this one is less about evil and more about tragedy of obsessive faith. I hope you dig it.

Well, the main character is based on a historical person—Walter Freeman Jr. He was the guy who revolutionized the lobotomy in the United States. He was this tragic figure—a doctor who really thought he was doing good, really thought he was saving the world. He used to drive across the country in his Lobotomobile, giving lobotomies to anybody and everybody who was suffering from mental ailments. Of course, most of his patients ended up being more damaged after the surgery. Still, until the day he died, he was convinced he had done the right thing. He used to contact all of his former patients—and there were tens of thousands of them—trying to convince himself that he had saved them. In addition to Freeman, there is a man who is convinced that his son is the Messiah, a sociopathic prostitute, and a group of machete wielding brothers. Typical Hallmark Channel stuff, you know? Actually, this one is less about evil and more about tragedy of obsessive faith. I hope you dig it.

No comments:

Post a Comment